Key Issues in Technical Problem Solving Leadership

Rebecca Silverman

Penn State Great Valley

School of Graduate Professional Studies

Abstract

The problems facing society today have reached a level of complexity far beyond that faced by previous generations, such that it exceeds the ability of one person to solve the problems on their own, and it is becoming more common to see teams of people come together to solve problems. Before being able to understand problem solving leadership, first one must understand the factors that facilitate the problem solving process. Every human being uses the same basic problem solving process, and without this basic process, people would not have been able to recognize and solve the problems that have presented themselves throughout history. It is this cognitive process that drives humans to not only solve the current problems, but to recognize the new problems that are created by the solution of the previous problems. This paper utilizes a model of problem solving theory developed by M. J. Kirton called Adaption-Innovation (A-I) theory to explore and identify key issues in technical problem solving leadership. A-I theory relates to cognitive style, or thinking style, and describes the different preferred ways in which people solve problems. It places human beings on a spectrum ranging from highly adaptive to highly innovative and is founded on the assumption that all people solve problems and are creative.

This paper examines and analyzes the observations of ten individuals from various levels of leadership, business units, and reporting structures within the Lockheed Martin organization in order to identify some of the key issues that face technical problem solving leaders in today’s corporate environment. Key concepts from A-I problem solving theory are integrated with the insights provided by these leaders.

Keywords

Problem solving, adaption, innovation, leadership, diversity

1 Introduction

Problem solving is defined by Wikipedia as a “higher-order cognitive process that requires the modulation and control of more routine or fundamental skills.” In other words, thinking is the means by which problems are solved. Every living organism has to learn to deal with problems on a day-to-day basis in order to survive and ensure the survival of its species. As mankind has evolved, so have the problems that it faces. As each problem is solved, it just leads to more complex problems to be solved by subsequent generations.

The problems that face society today are exponentially more difficult than those faced by previous generations. These problems have reached a level of complexity that exceeds the ability of one person to solve the problem on his or her own, and it is becoming more common to see teams of people come together to solve problems. Nowhere is this team problem solving approach more evident than in the workplace. According to Industrial Market Trends (2005), a recent trend, independent of industry and region, is that companies are focusing on hiring employees who are “team players” with “leadership qualities”. With this focus on team problem solving in the workplace comes a whole new perspective to problem solving – problem solving leadership.

Before being able to understand problem solving leadership, first one must understand the factors that facilitate the problem solving process. Jablokow (2005) in her review of A-I theory, states that the fundamental catalyst to scientific problem solving is the problem solving process of the human brain. Every human being uses the same basic problem solving process, and without this basic process people would not have been able to recognize and solve the problems that have presented themselves throughout history. It is this cognitive process that drives humans not only to solve the current problems, but to recognize the new problems that are created by the solution of the previous problems.

The problem solving process involves the following four key elements, shown below in Figure 1: the problem solver (or person), the process used to solve the problem, the outcome (or product), and the environment. According to Jablokow (2005), these key elements were formally identified by Rhodes (1961), but have not been focused on much in studies since then due to numerous reasons. The study of problem solving itself, while being a focus of investigation for quite some time, still has many gaps. Unlike chemistry and physics, the relationships between the elements of problem solving are not an exact science and therefore remain unclear. There are no set equations that can be used to describe problem solving. For example, person A in a given environment who employs a particular problem solving process will not necessarily produce the same product as person B in that same environment who employs a particular problem solving process. However, as the problems facing society become increasingly difficult and complex, it becomes more and more important to understand the problem solving process. This understanding will provide greater ability to predict the outcome of the problem solving process, which in turn will ensure continued technological development.

ENVIRONMENT

This paper utilizes a model of problem solving theory developed by M. J. Kirton (2003) called Adaption-Innovation (A-I) theory to explore and identify key issues in technical problem solving leadership. Jablokow (2005) states that A-I theory is “a significant, though less well-known, contribution from the field of psychology [that] combines breadth and precision to bridge the gap between person and process in highly practical and particularly insightful ways.” This theory, which is explored in greater depth in Section 2 of this paper, provides a greater insight into the links that connect the key elements of the problem solving process.

2 Problem Solving Theory

Adaption-Innovation theory relates to cognitive style, or thinking style, and describes the different preferred ways in which people solve problems. It places human beings on a scale that ranges from highly adaptive to highly innovative. This theory is founded on the assumption that “all people solve problems and are creative – both are outcomes of the same brain function.” (Kirton 2003)

Inherent preferred strategy, or cognitive style, and inherent capacity, or cognitive level, are completely independent of one another and vary from person to person. Therefore, an individual’s preferred problem solving style cannot be determined based on how intelligent (s)he is, how much experience (s)he has, or how senior (s)he is within a company. Although cognitive level is much easier to identify within an individual than cognitive style, the cognitive styles of the individuals on a team can play a key role in the problem solving process.

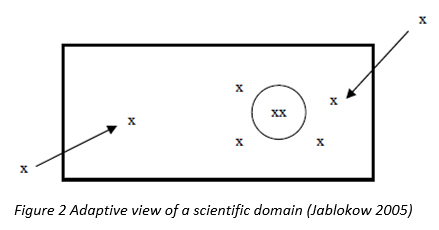

Kirton does not quantify people as being simply “adaptors” or “innovators,” but qualifies them as being “more adaptive” or “more innovative” based on the individual’s preferred style of problem solving. Because of their preferred style, adaptors and innovators view problem solving differently. Kirton (2003) characterizes more adaptive individuals as preferring problems that have more structure than those who are more innovative. He describes the more innovative people as being more tolerant of less structure in the problem solving process. Jablokow (2005) adds to Kirton’s definition by explaining that, therefore, “adaptors and innovators view scientific domains, their core concepts, and their respective boundaries differently.” This concept is depicted below in Figures 2 and 3. In both of these figures, each x is an idea created during the problem solving process that is related to the scientific domain, which is represented by the rectangles. The circles within the rectangle stand for the basic concepts, theories, and assumptions on which the domain is based.

Both individuals who are more adaptive and those who are more innovative are aware of and agree on the core of the domain; however, they react to it in very different ways. As Figure 2 depicts, more adaptive people are generally attracted to the core and use it to come up with new ideas. Therefore, their ideas are generally closer to the core of the domain. Conversely, more innovative people tend to stay away from the core in an attempt to find a ‘different’ solution. Consequently, their ideas are usually farther away from the core, and, according to Jablokow (2005), they incorporate “elements from other parts of the scientific domain (or even outside of it) that may not be considered sound by their more adaptive counterparts.” However, looking at it from the point of view of a more innovative individual, ideas that are closer to the core of the domain may be considered to be boring and too close to existing solutions to be useful.

Of course, whether or not an idea is within the boundary of the domain depends on where the boundary is defined. This boundary of a domain is much vaguer than the core, and as a result, more adaptive people have a tendency to define the boundaries differently than more innovative ones. More adaptive individuals see the domain boundary as being fixed and prefer to stay within that boundary. When a more adaptive person accidentally comes up with an idea that takes her outside of the domain boundary, she usually prefers to move to an idea that is back within the boundary of the domain, as shown by the arrows in Figure 2. On the contrary, more innovative individuals see the domain boundary as being more flexible, as indicated by the dashed line in Figure 3. They are usually not concerned about staying within the boundary, and may move outside of the boundary on purpose in an effort to come up with an idea that is completely unlike those that already exist.

According to Kirton (2003), another difference between more adaptive and more innovative people is “in the individual’s preferred direction of focus.” Individuals who are more adaptive more easily foresee threats and challenges that come from within the system, such as plans to downsize, whereas those who are more innovative more readily predict events that may threaten from the outside, such as early signs of changing markets or important advances in technology. Since more adaptive individuals tend to pick up signals that point to threats within the system, they tend to miss signals that point to threats from the outside, and the opposite is generally true for more innovative individuals. When signals that point to threats from the outside are missed by a more adaptive person and picked up by a more innovative person, it is human nature for the more adaptive individual to find warnings of these threats to be distracting and feel that the more innovative individual does not understand what is really important. The same is true when signals that point to threats from within the system are missed by more innovative people but picked up by the more adaptive people. It is important to remember the difference between level and style so that such predictions are not construed as higher intelligence, but rather a byproduct of an individual’s preferred style.

Jablokow (2005) summarized Kirton’s general characteristics of adaptive and innovative problem solvers, as shown below in Table 1.

The discussion of cognitive style up to this point has been based on an individual’s preferred problem solving style. However, there are situations where the behavior that best fits the problem is not aligned with an individual’s preferred problem solving style. When a person in this situation modifies his or her behavior to take on characteristics of another problem solving style, it is referred to as coping behavior. It is important to note that coping behavior is not a required behavior and therefore is not always used. As Kirton (2003) explains, “Coping behaviour, like the rest of cognitive resource, is available to cognitive effect when insight (or, better still, foresight) indicates that it is needed; the driving force behind execution, like all other executions, is motive.” Therefore, people utilize coping behavior much like they use their other experiences, knowledge, and skills. When an individual recognizes that there is a need for a different problem solving style than their preferred style, (s)he chooses whether or not to use it, like (s)he could also choose to use his or her experience or knowledge to help solve the problem. Motive is the driving force that determines whether or not (s)he chooses to make use of coping behavior.

So far this paper has examined problem solving level and style in terms of individuals being more or less experienced, more adaptive or more innovative, and individuals making use of coping behavior. But what happens when individuals come together to form teams? When people are formed into problem solving teams there are varying levels and styles that come into play during the problem solving process. Some teams are more diverse than others; however, even the most homogenous teams have individuals with some differences in level and style (as well as type, e.g., engineering, accountancy). It is human nature for the different characteristics of the problem solving styles, as discussed above, to cause frustration and conflict between team members. It is the job of the leader to deal with these differences. Kirton (2003) explains that “helping the team’s members to manage their diversity to common good, solving Problem A, is a prime task of the problem-solving leader.” This paper explores in greater detail how a problem-solving leader approaches this challenge.

3 Research Scope and Methods

In order to obtain a better understanding of technical problem solving leadership, a group of ten people from within the Lockheed Martin organization were interviewed. The individuals within the group were selected from various levels of leadership within Lockheed Martin, from program managers to vice presidents. This group of leaders also represents a variety of departments, business areas, and reporting structures within the organization.

A structured set of open-ended questions was created prior to the interviews. This gave the participants the opportunity to interpret the questions based on their individual experiences, while maintaining consistency in the topics covered in the interviews. The interviews were not recorded due to restrictions imposed by the interview sites; however, thorough notes were taken by the interviewer based on the participants’ response to the questions. These interview questions focused on the following four areas:

1. Discussing the importance of level and style in individual interactions

2. Discussing the impact of level and style in teams

3. Describing how level and style affect the creation and management of teams

4. Identifying the influence of level and style in technical problem solving leadership

At the completion of the interviews, the participants’ responses were examined and analyzed in order to identify general themes and key issues. Several themes were readily identified as being a common thread throughout all of the interviews, and these are discussed below in Section 4.

An interesting side note is that the interviews themselves, while identifying several common threads, did so in very different ways. Each person’s experiences obviously influenced how (s)he answered each of the questions, but it was even more than that. Someone who does not know these individuals could read over each of the interviews and make an educated guess as to what position that person was in. Each of the interviews was strongly influenced by the level within the company that each person held. For example, the Vice President and Directors who were interviewed looked at each of the questions from a much different perspective than the functional managers.

4 Key Issues

Although there were several themes identified as common threads throughout the interviews, there was one general idea that was expressed by every one of the individuals interviewed: that the success of a problem solving team is significantly influenced by its leader. While the team’s job is to focus on solving their particular technical problem, the leader needs to look at all aspects of the problem, including how the individuals on the team are working with each other and with their customer. Based on the interviews conducted for this paper, a successful leader takes into account each of the key issues identified below.

1. Understanding Individual Style

2. Ensuring Diversity of Level and Style Within Teams

3. Using Coping Behaviors to Effectively Manage Teams

4. Managing Teams that Do Not Match the Problem

5. Leading within Real World Limitations

The next five sections examine each of these issues in more detail using Kirton’s Adaption-Innovation theory discussed above to provide the basic framework for each of the discussions. It is important to keep in mind the distinction between level and style discussed in Section 2, as that distinction plays an important role in each of the key issues.

4.1 Understanding Individual Style

Understanding individual style is much more important in the workplace today than it has ever been before. The days when everyone in the company had to wear the same color suit with the same color tie are gone and have been replaced by a corporate environment that focuses on and embraces the diversity of their workforce. Each individual is now encouraged to express his/her individuality instead of conforming to some corporate ‘cookie cutter’ image, and with this understanding of individuality comes the need to understand the differences in individual style and how those differences affect the team.

One of the key reasons for understanding the styles of each individual on the team, which was discussed in the Kendrick (2006), Lombardo (2006), and McKnight (2006), and Cornman (2006) interviews, is to be able effectively to manage each of the people on the team. All of the people on the team cannot be managed the same way; they each have different needs based on their style. People who are more adaptive tend to follow set processes, and when given a problem to solve, go about solving it in a more structured, step-by-step process. As a result, when more adaptive people have a problem to solve that requires that type of structured approach, they are within their comfort zone and tend to require less involvement from their manager while tackling that problem. However, when a more adaptive person has a more innovative problem to solve, (s)he may feel uncomfortable and require more ‘hand-holding’ from his manager to be able to solve the problem successfully.

Conversely, when more innovative individuals have a problem to solve that requires a more innovative approach, they can work very independently with very little manager involvement. However, when a more innovative person has an adaptive type of problem to solve (s)he will tend to need to be ‘reigned in’ by his manager and will require much closer manager supervision. It is important to keep in mind that whether or not someone needs more or less involvement from his manager on a particular problem is not a reflection of that person’s intelligence. It is simply a by product of his preferred cognitive style and the type of problem that (s)he is trying to solve. Everyone at some point needs more or less manager supervision, regardless of how intelligent or experienced (s)he may be; therefore, it is up to the managers to recognize this fact and understand the styles of all the individuals on their team so that they can provide the appropriate leadership when necessary for each person.

Another dimension of understanding style, which was discussed during the Graham (2006), DelBusso (2006), and Puy (2006) interviews, is the importance of understanding one’s own style in addition to understanding the styles of the other people on the team. As DelBusso (2006) so aptly put it, “if you can’t figure out what your style is, then others won’t either.” When an individual understands his or her own style, (s)he is better able to understand his or her strengths and weaknesses as well.

With this understanding of one’s own individual style, coupled with an awareness of the styles of the other members of his team, an individual can interact more successfully within that team by utilizing coping behaviors when necessary. When a team can work together effectively and minimize the interpersonal issues, both the team and the team leaders are able to focus on the primary (technical) problem instead of investing valuable time and resources to solve secondary (team) problems.

4.2 Ensuring Diversity of Level and Style within Teams

Today’s corporate environment focuses on and embraces diversity in the workforce. In the past, diversity has traditionally been viewed as having people of different races, genders, and religions. As a part of a recent growing trend, Lockheed Martin now has training and initiatives in place that describe diversity as going beyond the traditional definition to include each individual’s experiences and background.

Kirton (2003) explained that solving “a diversity of problems requires a diverse team.” The problems that teams face in the workplace today are more complex than they have ever been, and they cover a much broader spectrum than they have in the past, as discussed above in Section 1. As the complexity of a problem increases, so does the value of having a variety of viewpoints. Each person looks at a problem in a different way based on his or her background and interprets it based on those unique experiences. Therefore, the more diverse a team is, the more diverse the backgrounds and experiences of the individuals on the team need to be.

At some point during every interview, the interviewee commented on the fact that level and style are another important aspect of diversity within the team. Mullins (2006) explained that in her experience “balancing styles and levels of experience brings the diversity that creates successful teams.” Although each of the leaders interviewed pointed out the importance of having a diversity of level and style within the team, they were also careful to make it clear that while having a diverse team could enhance the problem solution, it could also adversely affect it as well. DelBusso (2006) expressed that having a team of individuals of diverse levels and styles “could be really good and they could complement each other. They could come up with different things none of them would have thought of on their own. Or it could be bad, and they could struggle… Everyone has a different snippet of the picture. The challenge for us leaders is to pull that out and get the richest conversations that we can have around a problem.”

The key to successful problem solving is not just having a diverse team of problems solvers, although that is a significant part. Without having effective leaders in charge of that diverse team of problem solvers who can enable it to successfully generate a solution, the team may never reach its full problem solving potential.

4.3 Using Coping Behaviors to Manage Teams Effectively

Coping behavior can be a very important aspect of the problem solving process, because the problem that a team is trying to solve is not always clear cut. There may be aspects of the problem that would best fit a more innovative approach and others that would best fit a more adaptive approach. In Myers (2006) experience, “Most people, when pushed, can get into another mode. You can’t grow experience instantaneously, but you can get into another problem solving style and they can support that when pushed to do so.” Coping behavior, as mentioned above in Section 2, is not a required behavior, and therefore, people need motivation to drive them to take on this behavior. A good leader recognizes that and is able to supply that motivation to his team.

Another reason that coping behavior is a significant aspect of the problem solving process is due to the interpersonal interactions within the team. It is human nature to become frustrated or take offense when others suggest doing something a different way than what one is used to. Consequently, when a diverse team is created (as discussed in the previous section) to solve a particular problem, problems may arise between the more adaptive people and the more innovative individuals due to their different preferred approaches to problem solving. A difference in style between members of a team can be mitigated by having a person (or people as the case may be) make use of coping behaviors. When a leader is able to recognize that a problem is arising due to a difference in style, (s)he can motivate the necessary team members to use coping behavior in order to improve the interpersonal interactions within the team. This allows the team to focus on the primary (technical) problem instead of spending their time and resources on secondary (or interpersonal) problems.

A third aspect of how coping behaviors are an important part of the problem solving process has to do with how the leader interacts with his or her team. Fair (2006) explained it well when he said: “As a leader, you need to adapt styles based on the folks you have within the team.” A leader not only needs to recognize when individuals on his or her team need to utilize coping behaviors to improve the interpersonal interactions within the team, but (s)he also needs to identify when (s)he needs to make use of coping behaviors his or herself. The problem-solving leader should be able to motivate and guide his or her team, and in order to do so successfully, he or she must be able effectively to interact with the members of his or her team – including their needed diversity!

Recognizing the need to utilize coping behaviors is the first step. Effective leaders are able not only to recognize when coping behaviors are needed, but they also know what coping behaviors are necessary, who should be using them, and how they can motivate those individuals to take on the required behaviors. In short, they are able to identify the problem and supply their team with the tools to successfully solve that problem.

4.4 Managing Teams that Do Not Match the Problem

In a perfect world, the team created to solve a particular problem would be able to do so without any issues. However, that is not always possible in the real world. Sometimes, the team does not match the problem, and it is up to the leaders to recognize this and find the most effective way to resolve the issue. All of the leaders interviewed expressed that there are many different causes for a team not matching the problem, and that the appropriate action for them to take as leaders depends on what that cause is.

The most common cause of a team not matching the problem, according to the people interviewed for this paper, is having members of the team whose personalities clash. In the previous section, Section 4.3, using coping behaviors to mitigate interpersonal problems due to differences in style was discussed. When facing a conflict between members of a team, the interviewees seemed willing to take the time to try to work out the problems utilizing coping behaviors, given enough time and resources. However, according to Lombardo (2006), due to the nature of the problems he faces on a regular basis, he does not usually “have the freedom to wait for people to work out their differences because of limited time and budget.” When it came right down to it, all of the leaders interviewed for this paper felt that enabling the team successfully solve the problem within the allotted time and budget was their primary goal, and if that meant removing or replacing members of the team to accomplish that, then they were willing to do that. Although removing people may sometimes be necessary due to schedule and budget constraints, the removal of a team member can negatively impact other members of the team. In fact, the removal of a teammate can sometimes have a more negative impact on the rest of the team than the conflict that caused that person to be removed in the first place.

There were several other reasons for a team and problem being mismatched that were also brought up during the interviews. Mullins (2006) explained, “If it’s a focus or an empowerment issue, I might spend time with the team myself to energize them to understand where they are struggling and fill some gaps in to help them. You don’t always swap the people out unless it’s a personality or a skill set issue.” Her point about it being her job as the leader to understand where the issue is and move the team towards the solution was reinforced by several of the other interviewees. Puy (2006) also explained, “Sometimes there is something missing from the team and giving them a few nuggets helps to move the problem solving process along. Occasionally, [a leader] can retrofit the team with additional knowledge to get them where they need to be… Sometimes you need to unlock an understanding or path to move a team forward.” When the leader does not understand what is keeping the team from being successful, there is no way that (s)he can help them to solve the problem. The leader’s job is to make sure that his team successfully solves the problem they are facing, and in order to do this, (s)he must be aware of all of the challenges the team is dealing with, get the diversities within the team collaborate not clash and do what is appropriate to these particular situations.

4.5 Leading within Real World Limitations

The challenge of leading within the limitations of the real world is one that has been touched on by each of the previous key issues in this paper. In a perfect world, everyone would get along, there would be an unlimited amount of time and money to spend on solving a problem, and nobody would ever get frustrated or tired. Nevertheless, problem solving teams do live in the real world and are constrained by time, money, resources, and all of the characteristics of human nature. As Graham (2006) explained, “In a perfect world, you’d be able to take all the time to create a team with the perfect balance of style and level, but in the real world, you work with what you have. It’s understanding the different levels and styles of the people on the team that’s important.” The key is having leaders that know and understand the restrictions of the real world and are able to successfully lead a team of problem solvers while being constrained by these limitations.

There are many ways in which leaders try to mitigate problems that arise due to time, schedule, and resource constraints. One that was mentioned by Lombardo (2006) is trying to find roles for each person within the team that fit each person’s individual style and allow them to excel. Another that McKnight (2006) discussed is taking style and level into account before hiring an individual. He cannot always create his ideal team because he is constrained by who is available at that particular time, so knowing the levels and styles of the individuals who are available to create the team allows him to create the team best team possible given the circumstances.

There are always going to be constraints and limitations, no matter what problem a team is trying to solve. The leader’s responsibility, as Myers (2006) explained, is to “spend a lot of time evaluating tasks, evaluating the people on the staff and their abilities to accomplish those tasks, and then matching the right person to the right job.” Knowing the limitations and understanding the people on the team is what effective leaders do to ensure that their team is successful.

5 Conclusions and Recommendations

This paper has examined and analyzed the observations of ten individuals from various levels of leadership within the Lockheed Martin organization in order to identify some of the key issues that face technical problem solving leaders today. These issues have been described in detail and related to level and style as defined by Kirton’s Adaption-Innovation theory.

Understanding the key issues identified in this paper can help individuals in leadership positions to become more effective leaders in several ways. First, an understanding of one’s own individual style coupled with an awareness of the styles of the other members of his team helps a leader to successfully interact with the members of the team. When a leader is able to successfully interact with the members of his team, (s)he is able to build trust and establish relationships with the individuals on the team. This trust helps the leader to motivate the team, resolve style conflict within the team, and to supply their team with the tools to successfully solve that problem. Without an understanding of the styles of each person on the team, the leader cannot as easily identify problems when they arise, or help to solve them.

Second, effective leaders are able to recognize when coping behaviors are needed, what coping behaviors are necessary, who should be using them, and how they can motivate those individuals to take on the required behaviors. Sometimes, it’s the leader that needs to use coping behaviors to successfully interact with members of his or her team. As DelBusso (2006) explained, “A successful leader is a good connector. They have to be able to learn what is effective and then apply that as long as it works, and when it doesn’t, adapt it until it becomes effective again.” Effective leaders are able to recognize this need and combine it with their knowledge of their team when necessary to deal with any issues that occur.

Third, having a team that is diverse in style and level coupled with a leader who is able to utilize this diverse team to its maximum potential allows the team to generate a much richer solution than any one individual. Lastly, effective leaders know and understand the restrictions of the real world and are able to successfully lead a team of problem solvers while being constrained by these limitations. There are always going to be constraints and limitations, no matter what problem a team is trying to solve, and when the leader is able to identify the constraints that effect the team, (s)he is able to mitigate the affect that these limitations have on the success of his team.

Even with the insights provided by the participants of this study, there is still a need for further research in the area of problem solving leadership. There is still a lot to learn about the interactions within problem solving teams and between problem solving teams and their leaders. This study has given leaders valuable information about the key issues in technical problem solving leadership, and what makes those leaders effective. There is still much more to be learned about how the individuals on the team interact, and how those interactions affect the problem solving process.

In conclusion, this paper has shown that problem solving leaders need to understand their own individual style and levels, in addition to those of the people on their team. They need to create a team that brings together a diverse group of levels and styles, know how to utilize coping behaviors in order to help their team successfully generate a solution, and be able to identify when the team does not match the problem. When the team does not match the problem, they should be able to recognize why it does not and what the best solution is to make sure that it does. Leaders must also recognize the real world limitations that their team is working within and how to mitigate them. All of these are key aspects of technical problem solving leadership, and knowing and understanding what they are will enable people to become more effective technical problem solving leaders.

6 Acknowledgements

First and foremost I would like to thank Dr. Jablokow, my thesis advisor, who provided me with much needed knowledge, advice, and support. I would also like to thank all of the participants in this study for sharing their experiences and insights with me. They took time out of their busy schedules to help me, and without them, this paper would not have been possible.

On a more personal note, I would also like to thank my husband, Mike, for helping me find the words when I needed them, and for understanding that writing this paper was more important than cooking him dinner some nights. Last, although certainly not least, I would like to thank my puppy, Buddy, for giving up his seat on my lap for 14 weeks so that I could have the laptop there instead.

7 References

Cornman, Kathleen C., (2006), Lockheed Martin, King of Prussia, PA, 20 November 2006.

DelBusso, Steven F., (2006), Lockheed Martin, King of Prussia, PA, 1 November 2006.

Fair, Robert S., (2006), Lockheed Martin, King of Prussia, PA, 11 October 2006.

Graham, William L., (2006), Lockheed Martin, King of Prussia, PA, 3 October 2006.

Industrial Market Trends, (2005), Employees Needed: Make Money Spending Money, http://news.thomasnet.com/mt/rst.cgi/308, (04 November 2005).

Jablokow, Kathryn W., The catalytic nature of science: Implications for scientific problem solving in the 2st century, Technology in Society, 27, 2005.

Kendrick, Jerri, (2006), Lockheed Martin, King of Prussia, PA, 23 October 2006.

Kirton, M.J., (2003), Adaption-Innovation In the Context of Diversity and Change, East Sussex: Routledge.

Lombardo, John, (2006), Lockheed Martin, King of Prussia, PA, 9 October 2006.

McKnight, Balvin, (2006), Lockheed Martin, King of Prussia, PA, 3 October 2006.

Myers, JoDean K., (2006), Lockheed Martin, King of Prussia, PA, 15 November 2006.

Mullins, Anne, (2006), Lockheed Martin, King of Prussia, PA, 31 October 2006.

Puy, Allen S., (2006), Lockheed Martin, King of Prussia, PA, 14 November 2006.

Rhodes M., An analysis of creativity, Phi Delta Kappan, 42, 305-10, 1961.

Wikepedia, (2006), Problem Solving, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Problem_solving, (10 November 2006).

© Rebecca Silverman, 2006: I grant the Pennsylvania State University the non exclusive right to use this work for the University’s own purposes and to make single copies of the work available to the public on a not-for-profit basis if copies are not otherwise available.